Over the past six months, media outlets have been flooded by allegations of sexual misconduct. Men in nearly every sector, from government to entertainment, banking to journalism, and sports to charity, have been accused of harassment or abuse. In many ways, we are in the midst of a cultural revolution, as it becomes increasingly clear that this behavior, which has plagued workplaces for decades, will no longer be tolerated.

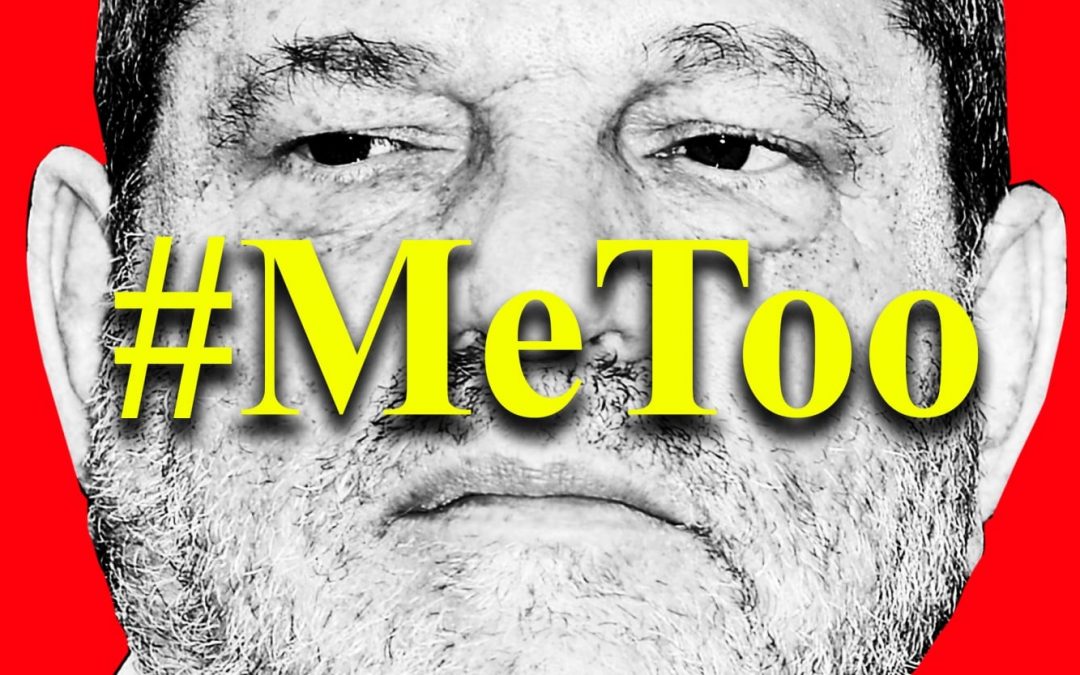

Immediately after the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke, thousands of women across the country stepped forward and spoke out. They used the scandal to denounce the former executive, but also to demonstrate that Weinstein’s behavior, heinous as it was, represented only the tip of the iceberg. In the months since, hundreds of men – producers like Weinstein, politicians, top chefs, news editors, NGO heads, actors, authors, coaches, players, and commentators alike – have faced allegations and criticism, and been fired or forced to resign.

Allegations against men like John Lasseter, head of Pixar animation, Tom Schumacher, the executive behind Disney’s “Frozen,” Justin Forsynth, former CEO of Save the Children, show that no sector is immune. The list continues to grow each day and is too big to include in this article, but can be found here.

Media coverage, the #MeToo movement, and Hollywood’s declaration that “Time’s Up,” have raised awareness, empowered victims, and encouraged others to step forward and speak out. Without a doubt, it’s a step in the right direction – but it’s still not enough. Hashtags, slogans, and buttons only go so far. They’ve shed light on rampant abuse and condemned alleged abusers, but we’re not any closer to preventing it.

Our inability to solve this problem lies in the diagnosis. We’ve labeled sexual misconduct as a cultural problem, which has been incredibly useful for raising awareness, but harmful for actually solving it. Systemic cultural problems must be addressed by broad cultural shifts. Cultures don’t change overnight, over weeks, or over months – small incremental changes take decades.

Furthermore, the characterization of sexual misconduct as a cultural problem has also made it dangerously easy for those complicit to shirk responsibility, in terms of both punishment and prevention. Making sexual misconduct everybody’s problem has simultaneously made it nobody’s.

The truth is, if we wait for a cultural shift against sexual misconduct, we’ll be waiting for a very, very long time. Preventing sexual misconduct requires a much more targeted approach that assumes responsibility for the problem and takes aim at the specific organizational environments and identities that breed it.

Treating sexual harassment as an organizational management issue, a symptom of poor company culture, allows us to attack the problem at its core. As the location of the majority of misconduct, companies have a stake in preventing it from occurring, in terms of employee satisfaction, organizational image, and their bottom line. According to recent studies, sexual misconduct can cost companies thousands in legal fees, emergency PR, reductions in productivity, and increased employee turnover.

Companies also have a unique advantage in waging war against sexual misconduct. Many have already begun to realize this and have started taking action, particularly once prompted by outside actors pushing for change – who have become increasingly difficult for companies to ignore.

In response to growing clamor related to the #MeToo Movement, Hollywood, for example, recently created an anonymous anti-sexual harassment hotline. Again, this seems like a step in the right direction. The success such a move will have, however, is likely limited. Fox News has had a similar mechanism running for years, but abuse continues to run rampant. Many employees simply don’t feel comfortable using it. Moreover, an abuse hotline is merely a reactive measure. It grants victims a way to report the misdeeds of others, but does little in the way of prevention.

Others have attempted to solve the issue of sexual misconduct by starting at the top. In recent months, we have seen a dramatic uptick in departures of senior executives, held accountable for their own indiscretions or for their complacence with the misdeeds of others. Travis Kalanick, former CEO of Uber, and Roger Ailes, founder of Fox, both fired for their hand in fostering toxicity within their companies, are just two examples of dozens.

Fidelity has taken a similar route, not by ousting executives, but by altering company structure in a more equitable way. By creating teams of equals, rather than strictly hierarchical groups made up of junior analysts led by senior managers, Fidelity is attempting to limit the role of power dynamics in promoting misconduct.

But while inequitable distributions of power exacerbate misconduct, the abuse does not always stop there. Toxic behaviors of executives and senior managers alike become embedded in company culture, adopted and repeated throughout its ranks. In these cases, when abuse is pervasive throughout an organization, top-down approaches do not suffice. Replacing one corporate leader with another is unlikely to affect much change further own the totem pole.

These attempts to change organizational culture and prevent abuse are well intentioned, but misguided. Individual identities and behaviors drive company culture, and not the other way around. To solve the problem of sexual misconduct in the workplace and to stop abuse from occurring in the first place, companies must target individual identities to shape behavior – and culture – from the bottom up.

Companies that dig deeper, taking advantage of technological solutions and identity analysis, are able to pinpoint the individual and organizational identities most prone to commit transgressions. From there, organizations can revamp mission statements in a way that links them back to individuals’ core beliefs, making zero-tolerance policies more likely to be accepted.

By targeting individual identities, companies can shape employee behavior, prevent abuse, and create an organizational culture that is not just “zero tolerance,” but one that is actually zero occurrence.

As the site of so much misconduct, companies across all sectors have both a great stake and a great advantage in preventing abuse. They also have a responsibility to do so. In the short term, treating sexual misconduct as a symptom of organizational culture allows companies to better protect workers, spur productivity, prevent scandals, and most importantly, quell abuse. In the long term, the benefits of such a strategy only multiply, as the impact of concurrent organizational shifts becomes increasingly reflected throughout the whole of society.